Berkeley County in the Civil War…between the lines.

Geographically, culturally, and economically, Berkeley County was caught between the two opposing sides, and very much in the path of the conflict.

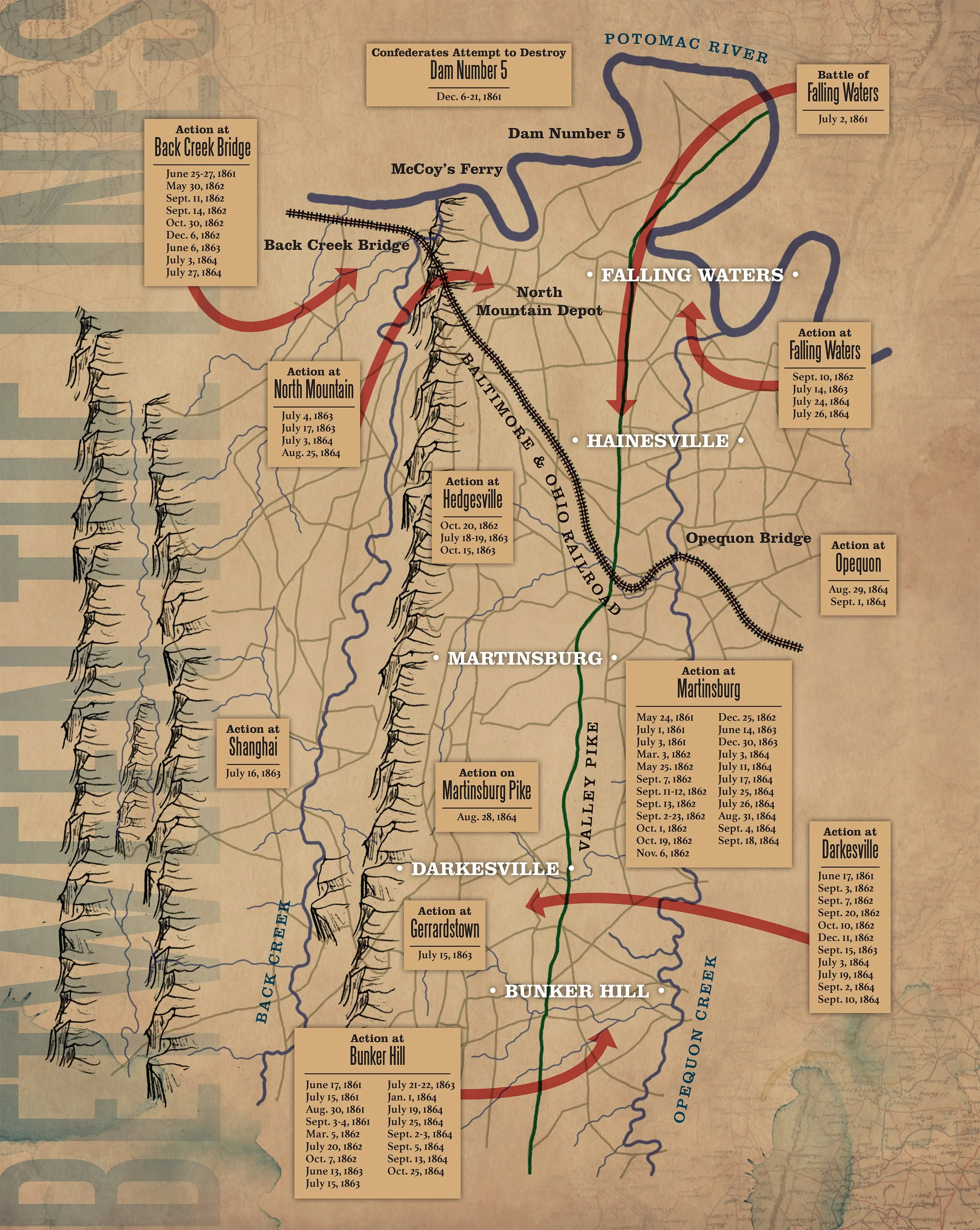

Berkeley County sits at the northern entrance to the Shenandoah Valley, a rich agricultural region. This geographic position placed Berkeley County squarely in the path of one of the principle routes between North and South, which would be used time and again by both Union and Confederate armies as they advanced into each other’s territory. Just as important was the presence of both the B&O Railroad and the Valley Turnpike. The railroad was a major east-west commercial artery, and was one of the central targets of the struggle in the area, while the turnpike provided an easy path not only for troops on foot but for artillery and supply wagons. Its general location, and the vital transportation routes it contained, meant that Berkeley County would be a natural strategic goal for both sides.

From a cultural and economic sense, at the outbreak of the Civil War, Berkeley County had a primarily agricultural economy, much like the eastern Tidewater and Piedmont regions of Virginia that favored secession. It differed, however, in that slave labor was relatively scarce, and small farms and orchards formed the main part of the economy, rather than large plantations. Culturally, the area matched its geographic location, being a mix of east and west, which would later be mirrored in the deep divide in support of its people, between Union and Confederacy. Because of these factors, Berkeley County was very much in the middle of the Civil War, though few histories on the subject mention it in any great detail, as it is lost in the shadow of the war in Virginia and the Confederate invasions of the North.

1861 saw the country split asunder and both North and South scrambling to prepare for war. After its delegates split their vote at the Secession Convention, Berkeley County voted against disunion by nearly a three-to-one margin. The vote statewide, however, would be in favor of severing ties with the Federal Government, and so, Berkeley County’s fate was sealed. While this drama was playing out, the men of the county prepared for conflict.

The Berkeley Border Guards and the Hedgesville Blues, two local militia companies, would report for duty to the South at Harpers Ferry, becoming companies D and E of the 2nd Virginia Infantry, respectively. They would join seven other companies from the county, some of which served the Union, some the Confederacy. The men of the 2nd Virginia would acquit themselves well at First Manassas, being part of Stonewall Jackson’s defense of Henry House Hill. During the battle, the dashing young Peyton Harrison and the Conrad Brothers, Tucker and Holmes, would be among the Confederate casualties. The Conrads, according to the writings of others in the regiment, died face-to-face and almost touching each other. All three were brought back to Martinsburg after the battle and buried in Old Norbourne Cemetery by their Captain, John Q. A. Nadenbousch, with the Conrad brothers sharing a grave. This would be the first taste for the county of the real meaning and cost of war, though much of the first year was spent adapting to the changes brought on by the conflict and wondering what fate had in store for the people in the area, but also for the Union and Confederacy. 1861 in the county itself was largely focused around the railroad changing hands as both sides sought to secure this vital means of transportation. The year would end with an inconclusive conflict over Dam No. 5 on the C&O Canal in early December.

The following year would initially look to have more of the same in store for Berkeley County. Throughout the year, the Union Army heavily guarded the B&O railroad and did their best to repair the damage inflicted by the Confederates in 1861. The Confederates did their best to stop this restoration in force and caused as much damage in other areas of the county as possible. The damage was particularly heavy in the vicinity of Back Creek Valley and Sleepy Creek, with important bridges being destroyed and taking months to repair. This depredation was largely accomplished by Confederate cavalry, who could move quickly and cause significant damage and confusion.

The spring of 1862 would also see Stonewall Jackson mastermind his famed Valley Campaign, during which he constantly outmaneuvered Union forces under Nathaniel Banks, John C. Fremont and Irvin McDowell. As the Federals chased Jackson up and down the Valley, or fled before his lightning quick advances, Berkeley County was on the periphery of this action. Initially, there was much speculation as to what was going on with the action unfolding so quickly, the citizens struggled to get accurate news of what was transpiring in the Valley. As the action shifted in the Valley, the people of Berkeley County began to see some small skirmishes and larger scale troops movements such as Banks’ retreat across the Potomac after being routed by Jackson at the First Battle of Winchester. This was nothing compared to the upheaval that would be caused by the movements of the Confederate Maryland Campaign. In early September, portions of the Army of Northern Virginia moved through, chasing out small Federal detachments and camping en masse. Berkeley County would see even more disruption after the Battle of Sharpsburg as the Confederates fled through, leaving massive numbers of casualties to be cared for in the Martinsburg area. They would go on to establish camps in the Bunker Hill area, doing their best to gain some much needed resupply and respite. In October, Jeb Stuart’s Chambersburg Raid would set out from the Bower, in Darkesville.

1863 would prove to be another big year for Berkeley County, as one of the most significant military operations of the Civil War would unfold, with the Southerners passing through on their way to Gettysburg, and again on their retreat afterwards.

The first part of the year would be fairly quiet in Berkeley County, as the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia recovered from Sharpsburg and Fredericksburg before clashing again at Chancellorsville. In June, as the Confederates began their second invasion of the North, activity would pick up a great deal. On June 13th, 1863, there was a heavy skirmish at Bunker Hill as Confederate cavalry and an infantry division of Richard Ewell’s Second Corps attempted to secure the Valley Turnpike, while the remainder of his command moved on Winchester. On June 14th, the infantry division, commanded by Robert Rodes, and the cavalry of Albert G. Jenkins drove Union forces out of the area in the First Battle of Martinsburg. Jenkins had been skirmishing with the Federals on and off to no great effect, and an early demand of surrender was refused. Once the Confederate infantry arrived, a few well-placed artillery shots drove the Union troops into a disorganized retreat towards Shepherdstown and Harpers Ferry. With the Federal presence in Winchester and Martinsburg cleared, Ewell’s Second Corps could proceed on across the Potomac to join the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia in their move towards Pennsylvania. The outcome of Gettysburg needs no further discussion, but, much like after Sharpsburg, Berkeley County would soon turn into a large-scale medical operation to tend to the Confederate soldiers too grievously wounded to continue the retreat. Large numbers of Union prisoners were brought through Martinsburg on their way to Southern prison camps. The Federals did their best to hamper the Confederate retreat, but were largely unsuccessful, and Berkeley County would endure no further conflict for the remainder of 1863.

Direct conflict in Berkeley County would intensify in scale during 1864. The Valley Campaigns of 1864 would turn the Shenandoah Valley into a battlefield in earnest, rather than just the periphery of a major military action. Berkeley County would escape the worst part of the damage done elsewhere in the Valley during Sheridan’s Burning, but it would not be free of conflict altogether. This would begin in May as Union forces under Major General Franz Sigel left Martinsburg to move South in the Valley to threaten Confederate supply lines and the flanks of the Army of Northern Virginia. His early successes would be for naught, as the Federals were crushed during the Battle of New Market. This Battle is famous for the participation of the Corps of Cadets from VMI, of which Charles James Faulkner, Jr. of Berkeley County was a part. This campaign would continue under the direction of Major General David Hunter, but the arrival of the Confederate Second Corps under Jubal Early sent the Union troops in full retreat. Hunter turned aside into West Virginia, rather than continuing toward Maryland or Pennsylvania, leaving the lower part of the Valley open to Confederate advance.

The Confederate would take Martinsburg in early July, and as part of this movement, there was a small battle at North Mountain Depot near Hedgesville, where two companies of the 135th Ohio were captured and sent south to Andersonville, the notorious Confederate prison camp. Only 65 of these men would live to see Ohio again.As the rapid actions of Jubal Early’s Valley Campaign unfolded, the area changed hands several times. On July 25th, the Second Battle of Martinsburg occurred. The Confederates captured Martinsburg in a battle that occurred with the grounds of Boydville squarely between the lines. The area would be finally secured by Federal Troops again in September and would remain under the Stars and Stripes for the remainder of the Civil War.

1865 would prove to be much calmer than the previous four years. With Union control solidly established, direct conflict was virtually unknown. The early part of the year would be devoted to healing from the damage in property and morale caused by the war.

There would also be a great deal of anxiety on both sides as the end of the war became ever more likely. The people of Berkeley County, whether they supported the Union or the Confederacy, were finally able to give thought to what would come after peace had been restored. For Unionists, this meant a return to the status quo. They could go on with their lives, no longer fearing for loss of life or property. For Southern sympathizers, it was a more deeply personal time. The promise of a country of their own was dying, and bitterness and resentment were the order of the day. On April 9th, Robert E. Lee would surrender the Army of Northern Virginia, and though it took several weeks for the remaining Confederate armies to surrender, it was effectively the end of the Civil War. The men of Company D and E of the 2nd Virginia Infantry, the scant remnants of Company B of the Wise Artillery and a few token men of Company B of the 1st Virginia Cavalry were present for the surrender. They would have been paroled, not to take up arms against the United States until properly exchanged, and the treatment they received from their counterparts in the Army of the Potomac was both kind and honorable. For them, it must have been a time of mixed emotions. Almost five long years of fighting had been for naught, but the prospect of rejoining their families and resuming their old lives must have been bright.

With the Civil War finally over, the people of Berkeley County could look back at the last five years. A multitude of skirmishes and four sizeable battles had been fought, often amidst their very homes. Control of the county had changed hands so often, it was difficult to tell whether they lived under the Stars and Stripes or the Stars and Bars. Martinsburg itself had changed hands at least thirty times, with some estimates as high as the low 70s. Their county seat had served as a supply depot and transportation hub, making it a valuable military target. Their railroads had been destroyed and rebuilt time and again, disrupting the livelihoods of those who were employed by the B&O. They had taken care of countless soldiers on both sides in the form of large scale hospital operations in the aftermath of Sharpsburg and Gettysburg, and in food, clothing and respite freely given on a smaller scale. Their property had been taken or destroyed, though in this sense, they were fortunate to have escaped the destruction that took place in the southern Shenandoah Valley. Their country had been restored to a unified whole, or bent in subjugation, depending on which side they supported. Their fathers, sons, brothers, and neighbors had gone off to war, many never to return. With all this behind them, it was time to start rebuilding their lives, returning as much to normalcy as possible. Having spent five years directly in the path of war, the people of Berkeley County maintained their unique character and, for the most part, their property and lives as well. There are many interesting stories about the Civil War in Berkeley County, and the lives of its people during the conflict, only parts of which are shared here.

Key events, dates, and locations in Berkeley County during the Civil War.

Download the complete Civil War History brochure.